Fine art appreciation, classical music and reading neutralized the sting of Jim Crow.

|

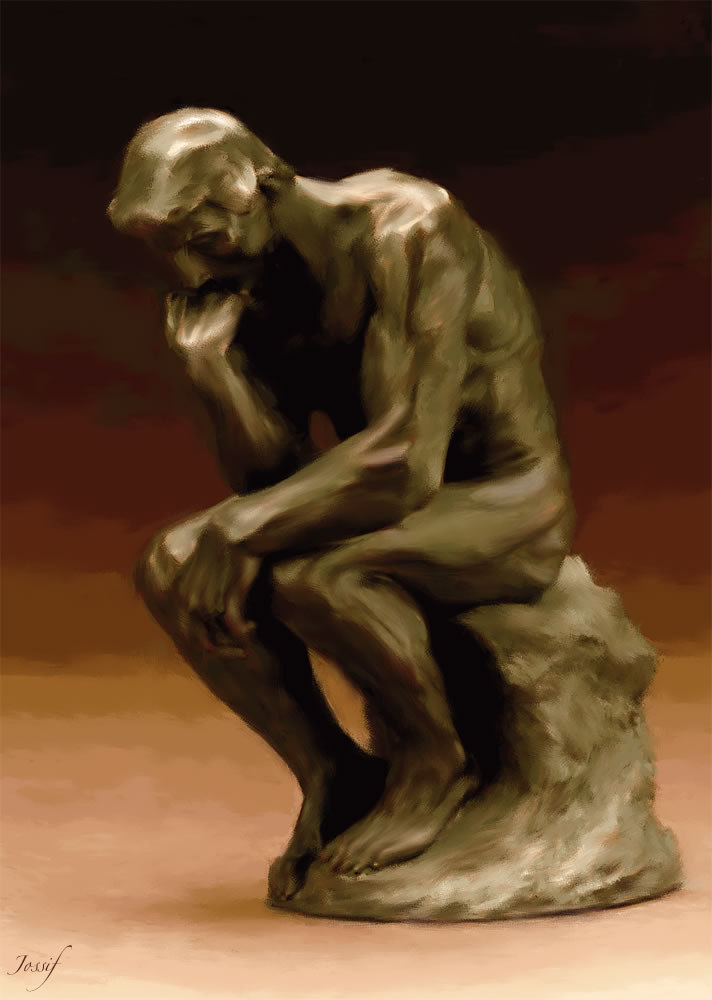

| Rodin - The Thinker |

When I was nine, my mother brought home a book on the French sculptor, François-Auguste-René Rodin (1840-1917).

My mother loved art, any art--books, literature, paintings, sculpture, music, film, dance, photography, architecture, history, philosophy and intelligent conversation. But I was as confused about her handing this book over to me after she had read it as I was about her making me take ballet and piano lessons, which I am now convinced she insisted upon so that I could notate music to the songs she was writing, another story for another time.

I remember that on the cover of the book was Rodin's The Thinker, a bronze and marble sculpture, which is now in the Musée Rodin in Paris. "Why do I have to read this book about Rodin?" I asked, mispronouncing his name in my childish innocence and ignorance.

"Because I said you have to read it," my mother answered. "And because I refuse to raise an ignorant child who can't pronounce Rodin correctly."

"Oh," was all I could muster. "But why do I have to read this?"

"So you will learn to say his name correctly... Rodin," she pronounced it for me again and made me repeat it. "You can't go to college mispronouncing famous names." I knew I did not dare argue with her or just pretend I to read the book because she would quiz me on it like she did everything else. So, I read it.

|

| Rodin Museum in Paris, France |

When Rodin was 76 years old, he donated his own works of art and his art collection by other artists to the French government. My mother told me about his donation, which is now in the Rodin Museum.

|

| Rodin Museum: Le Baiser |

My mother said people who create, participate in and appreciate art are better thinkers than those who do not.

"Those interested in literature, music and art can handle conversation," she said. "It has to do with the way their brains work and how they decide to live; maybe because they use their minds in a different way."

Contrary to what I thought before starting the book about Rodin, I did find it interesting. Rodin's early education was not considered good enough to gain him entrance into the elite art academy and still he went on to be a foremost figure in the development of modern sculpture. His piece, The Thinker, became my favorite work of art, representing a superior intellectual quality like my mother's that I wished to possess.

|

François-Auguste-René Rodin

(1840-1917)

|

How could my mother have known this man, this book and this sculpture would have that impact on me?

Was she teaching me something about my own intellect, also considered inferior because I was attending a Jim Crow school at the time?

My mother knew the book about Rodin was not the type of reading material our school library offered.

She wanted me to know about people and places far away from my Jim Crow world, one of the reasons we traveled to other states where I could see what the rest of the world had to offer me. Starting when I was four years old my mother took me to the movies at the segregated theater downtown. Once the lights went down, I was transported to wherever the movie took me. . We would lose ourselves in the beautiful clothes and exotic locations.

"Do not be afraid to explore art, film, books and traditions of other cultures," she always said. "That's how you learn." My mother believed in a global education.

While reading the book on Rodin, I learned that he was born in 1840 in Paris, France. That was the same time that, on this side of the Atlantic, slavery in America was still flourishing in the Deep South. Even as the Civil Rights Movement was in progress, it was unlikely that a little black girl would have been able to discover the genius of Rodin or others without someone like my mother to make the suggestion. At my mother's insistence on exposing me to higher concepts, I was reading about Rodin during the civil rights movement.

There were people whom my mother admired in the world who were not directly associated with the sciences or the arts, but she believed if she could get inside their homes, she would find art hanging on the walls, many shelves of books and the music of the masters playing in the background.

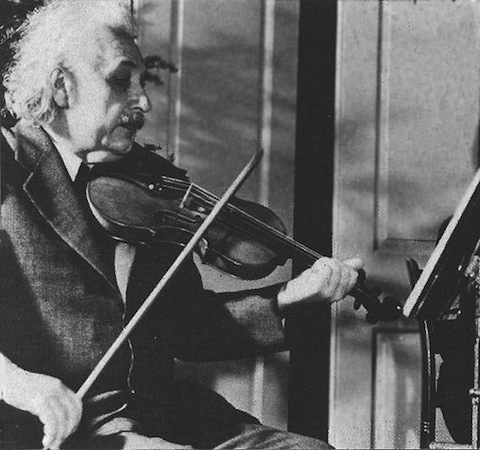

"Did you know Albert Einstein was also a musician?" My mother asked me.

|

"Who is that?" I asked her.

The Spring before I started first grade, Albert Einstein died. My mother was anxious to have me understand not only what the world had lost when this genius died, but also what the world had in him.

"A genius," she said.

"What's that?"

"A very smart person," she said.

"Like you?" I asked.

She laughed. "No, much smarter than me. He loved Mozart and used his music to help him develop his theories."

There she goes again, I thought. I didn't understand what all of that meant. I was only five years old!

And my mother's intellectual admiration did not stop at theoretical physicists. "I'll bet Dr. Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks know who Albert Einstein is," my mother said. Rosa Parks started the Montgomery Bus Boycott at the end of 1955 after I was in first grade. My mother kept up with all that news the same way she had kept up with the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v the Board of Education. She bought magazines and newspapers on her way home from work.

|

| Rosa Parks Booking Photo, Montgomery Bus Boycott |

"You can hear culture in people's voices and in the way they use language," my mother said. "Reserved and elegant, those are the thinkers. Thinkers become doers."

As history has recorded, both Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote books about their lives and experiences during the Civil Rights Movement, documenting those thoughts and the resulting actions.

We had a television in 1955, but there were a couple of problems. In our town, there was only one local station and it was quite conservative and limited broadcasts to those that were none offensive to the majority community. That meant very little to no coverage of Rosa Parks, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement. Secondly, my mother had her doubts that sitting in front of a screen too much was safe for the eyes or the brain. So, she restricted my television viewing to her approved list of programming.

|

| Rosa Parks & Martin Luther King (Articles) |

My mother received civil rights news through delivery of national black publications to our home on a weekly basis. She required me to read articles and then discuss them with her afterwards. Topics were confusing to me and not always a pleasant experience. I always enjoyed our discussions of art history more, perhaps because, as a child, art history was less intimidating than civil rights. When my mother made me read articles and books she had selected, I read them to be ready for her quizzes.

I read books and articles, and examined art because my mother said a person could not be just a collector of books and art. Art hanging on walls or books on shelves did not pass my mother's sniff test. The person who possessed the books and art had to know something about what was in the books, know about the art or know something about the artist who produce the art. An amateur artist herself, she liked to paint animals, birds and landscapes. My really wanted to me to be interested in art, too.

|

| Brownie Camera |

My grandmother bought me a Brownie camera when I was eight in exchange for not bothering her gun again.

She got really upset when I sneaked the gun out of the house and tried to buy bullets at the corner market. But the storekeeper called my house and told my grandmother what I was up to. I tried to explain that I had a good reason, but no one would listen.

My grandmother said my punishment was to use the camera to shoot whatever or whoever I needed to shoot, but not without asking them first. "Do not go sneaking around behind people's backs taking pictures of them," she said. "That is a good way to make enemies and to lose your camera privileges." Like I lost my gun privileges, I thought, hoping she wouldn't tell my mother about the gun.

My mother didn't ask why my grandmother bought me the camera, but she restricted my photography even further: Do not photograph people! She felt I would not be sufficiently respectful of their privacy and she was probably right. Although, looking back on it, I wouldn't call what I was doing photography. My photographs were awful. But my mother was delighted that I was interested in photography. "It's a form of fine art," she said.

I wrote a story, Shooting Without A Gun, in my book, Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's, about Bigmama's gun and the camera. Take a look and join my channel.

My mother didn't say much about the incident with me and Bigmama's gun, but I am certain she had all to do with my grandmother giving me that camera.

|

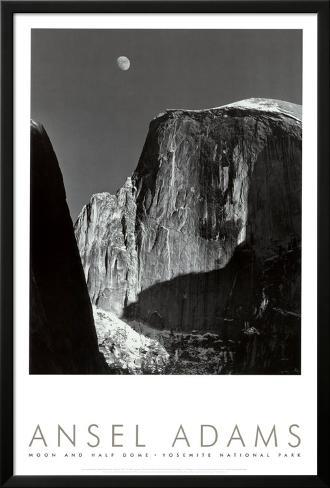

| Ansel Adams Moon and Half Dome Yosemite National Park, 1960 |

My mother was particularly fond of sunsets, water, night skies, old buildings and sand. When I was about 11 years old, my mother bought postcards with Ansel Adams photography, saying I should model my own style of photography on his style, which she thought was magnificent.

I had no photographic style. "Aim high!" She scolded. "And be sure and pack your camera when we go to the beach next weekend." My mother had a friend in Houston who was from a wealthy mortuary family with property in Galveston and one son my age. During the season, we often met her and her son at their beach cottage for weekends. My mother was always happy when her friend's older son, who was a professional photographer, joined us at the beach and let me tag along while he photographed nature scenes and explained lighting and photo composition.

The summer of my 15th birthday, Aunt Clara took me to the mountains, where I wasted rolls of film trying to take shots as my mother had instructed, only to find out after the photographs were developed that I was no Ansel Adams, nor was I even close. I was very disappointed when I got home from vacation, and my mother and I reviewed my shots. Then, I realized the photography exercise was for my benefit. She was trying to help me develop an eye.

I did eventually develop an eye for photography. My images were published in a significant reference book on the history of photography.

|

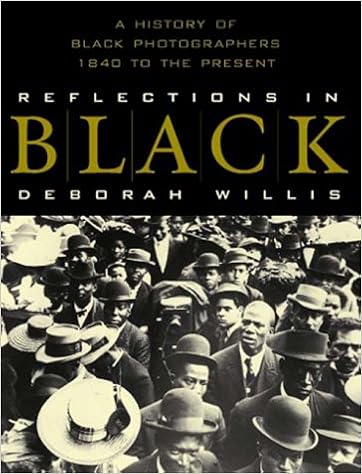

| Reflections in Black:

A History of Black

Photographers

1840 to the Present |

My photography has been collected by a number of prestigious museums and libraries, published in books, newspapers and magazines, and exhibited around the world with a Smithsonian Exhibition, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present. I credit my mother for my success by insisting that I take all those terrible pictures when I was a kid.

My mother was totally absorbed in art--the art of others in galleries, her own art creations, my crude and amateur photography or pictures in books. And she liked volumes, not just for the quantity, but for the matching binding.

"Sets of books make you feel like you're in a library," she said. "The feel of art books and the smell of them make me want to paint or get knee-deep in some clay. You can't pretend to love art or know what's in books. Love and knowledge of these subjects come out in conversation, and if you're pretending, you will soon look the fool. Anybody with money can be advised on what art pieces to buy," she said. "The real test is finding a way to surround yourself with art if you are on a tight budget."

And a tight budget was something my mother knew all about. "But we can't let the lack of money keep us from enjoying the finer things," she said. "People need art in their lives, all people--rich and poor!"

|

| Converted Bus Bookmobile |

When I was a little girl, our town did not allow us to use the segregated public library in the 1950s. Jim Crow laws ordered the public library to offer bookmobile services to neighborhoods. A bookmobile was a converted station wagon, van or bus with rows shelves with books, mostly outdated and tattered. The bookmobile was most active in summer and parked in public parks.

Back then, until we were allowed to use the library, my mother and I took a Greyhound Bus 100 miles away to Houston to use the Houston Public Library. The trip to Houston was an all day affair, but worth it, even if we didn't qualify for library cards, not because we were not white, but because we were from out of town. We sat among all those art books on the shelves and read until it was time for us to catch our bus back home. My mother used the library, like she used movies, to imagine places we had never been, to see images from faraway places that one day we might see and to teach me to see myself as the Jim Crow south could not.

From those movies and books, she imagined scenes, learned to paint oil landscapes and restored damaged art she bought in second-hand stores. She collected art, museum, gallery and exhibition books and often dragged me to out-of-town galleries and museums that allowed African Americans to enter if could afford a ticket. Afterwards, she bought greeting cards and program booklets that were not too expensive and she required me to make detailed critiques of shows we had seen.

My mother collected interior design, architecture and art magazines, too. "Be careful with those," she told me. "They're not cheap." Sketching out plans for home improvement projects was a favorite past-time that my mother loved. Using her architecture and art magazines, and Vogue pattern decorating book, she measured and made multiple drawings before presenting them to my father to see if he could build whatever it was she wanted. Usually, he couldn't or wouldn't produce her final design or, if he did, she wasn't satisfied with the shortcuts he took. So, she went on to construct whatever small project she wanted to create.

Art, music and literature were my mother's weapons against excuses, which she refused to accept. "Most often," she said, "You get what you give."

|

I searched the Internet and could not find a copy of the Rodin book my mother gave me all those years ago. Perhaps the book is out of print. But I found some other interesting selections devoted to Rodin and others that trace art history from the Renaissance to Rodin and the birth of modern art.

Over the years, my mother's interests and book collections changed and I do not know what happened to the book about Rodin that she made me read. The book was probably not responsible for getting me a college scholarship or even getting me through Texas A&M University's Department of Journalism and Broadcast Communications. But my mother knew Rodin would have an influence on me at a time when I needed it most.

~30~

Sunny Nash

Author-Journalist |

|

Hard Cover

Amazon Kindle

|

Sunny Nash, former nationally syndicated newspaper columnist, is the author of a nonfiction book about life before and during the Civil Rights Movement with her part-Comanche grandmother, Bigmama Didn’t Shop At Woolworth’s, selected by the American Association of University Presses as a Book for Understanding U.S. Race Relations, and recommended by the Miami-Dade (Florida) Public Library System for Native American Collections.

Sunny Nash earned a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism & Mass Communication, Texas A&M University; Postgraduate Media Studies Certificate, Cronkite School of Journalism & Mass Communications, Arizona State University; Postgraduate Diploma, Instructional Technology, University of California, San Diego; Constitution Studies, James Madison’s Montpelier Center for the Constitution; and Postgraduate Digital Literacy Certificate, Simmons College Graduate School of Library & Information Science, Boston. Sunny Nash’s international studies include Intellectual Property Law, World Intellectual Property Organization Academy, Geneva, Switzerland; Diplomacy, Culture and Communication, United Nations; Research Methodology, Digital Preservation, Online Archival Information Systems, University of London; and Archival Data Governance, National Archives of Australia, Melbourne.

© 2020 Sunny Nash. All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

www.sunnynash.blogspot.com

~Thank You~

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.