Kenny Burrell, a calm jazz oasis, during the most dangerous decade of the Twentieth Century--the '60s!

| man at work LP |

Kenny Burrell Still Playing Strong

Oh, please let there be a birthday bash and concert on PBS this year! My memories of Kenny Burrell go back to 1966. What a year.

In 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King questioned race relations in Chicago; the Vietnam War was cranking up; hippies became a movement with flowers as a mascot; hard rock and Motown fought for the airwaves; James Brown must have just discovered Colonics when he danced his way across the stage of the Ed Sullivan Show with I Feel Good!; and Kenny Burrell came out with Man At Work, 47 years ago. And, yes, Kenny Burrell's Man At Work was vinyl. That's what we had back then. And I hear, these days, that vinyl is making a comeback because digital can't match the warm sound of vinyl.

| James Brown Live At The Apollo, 1962 |

Some aspiring musicians I knew when I first started out in the music business didn't have the talent to make it big in the music industry, me included, or have the guts to stay in the music industry if they possessed the talent. They could feel their lack of talent and guts and still they did everything they could to stay in the music business, including getting high or worse with anyone they thought could give them a hand up the ladder. The hand never came disappeared and many were used up by age 21. The mid-level musicians, which I became part of, could hang on for a little longer because we worked harder at the music craft than those who thought they were too gifted to have to work hard.

|

| man at work LP by Kenny Burrell, 1966 Kenny Burrell MP3 Download Page Time Out -- The Dave Brubeck Quartet: 50th Anniversary (Piano Solos) |

In 1966, at the time of the release of Kenny Burrell's Man At Work, 45 years ago, I was 16 and starting her own music career in Houston, Texas, singing at jazz venues around the city such as the El Dorado Ballroom on Elgin Street with notables such as the 21-piece Conrad Johnson Orchestra, performing live on radio on Saturday nights, booked by Groovy George Nelson of KYOK. Yes, that's right. I picked up where my mother left off.

Musicians and vocalists, including me, loved Kenny Burrell's style and tried to copy and incorporate it into their own styling in some way, regardless of their instrument. Over the noise of the outside world, I listened to Kenny Burrell and tried my best to copy his phrasing with my voice. That’s how much his music moved me. Listening to this incredible musician, now, I still love his luscious sounds, 45 years later, with a special appreciation for the man who was then only 35 years old with so much of his life and career still to be explored. Kenny Burrell’s sound on his album, Man At Work, in 1966 was so rich, so mellow, so smooth, it was intoxicating.

I think I would have missed out on that music had it not been for my mother, who loved both jazz and classical music--the mellower, the better. She also loved Dave Brubeck, especially Take Five. Some of my friends thought my mother was being a bit pretentious, but her love for this music was real. And that's what we listened to at home when I was child, while my friends listened to this new thing, called Rock-and-Roll, in their homes, either on radio if they could receive a signal from Houston's black stations, KYOK or KCOH, or a record player if they had one.

We had a beat-up second-hand record player my mother picked up at a used furniture store. She placed the contraption in a corner of our living room beside her reading chair in front of the bookcase. No one--not me, my father or my grandmother--was allowed to touch my mother's records or her record player. She was very careful not to let the needle that touched the records become damaged. Once when I dropped the needle arm by accident on one of her records, I thought I would be banished from the house.

"A damaged needle," she said, "will scratch the records and they will become fuzzy with loosened vinyl and look something like a woolen sweater and I don't want you trying to play a woolen sweater on my record player." The end of her patience with me came when she caught me playing a borrowed scratched Chuck Berry record on her record player. The condition of the record dulled her needle. That's when she found another used record player for me to play my collection. I didn't get to play my records much because she was always playing hers. I finally lost interest in anything but jazz, especially jazz guitarist, Kenny Burrell, and jazz vocalist and organist, Jimmy Smith.

I think I would have missed out on that music had it not been for my mother, who loved both jazz and classical music--the mellower, the better. She also loved Dave Brubeck, especially Take Five. Some of my friends thought my mother was being a bit pretentious, but her love for this music was real. And that's what we listened to at home when I was child, while my friends listened to this new thing, called Rock-and-Roll, in their homes, either on radio if they could receive a signal from Houston's black stations, KYOK or KCOH, or a record player if they had one.

We had a beat-up second-hand record player my mother picked up at a used furniture store. She placed the contraption in a corner of our living room beside her reading chair in front of the bookcase. No one--not me, my father or my grandmother--was allowed to touch my mother's records or her record player. She was very careful not to let the needle that touched the records become damaged. Once when I dropped the needle arm by accident on one of her records, I thought I would be banished from the house.

"A damaged needle," she said, "will scratch the records and they will become fuzzy with loosened vinyl and look something like a woolen sweater and I don't want you trying to play a woolen sweater on my record player." The end of her patience with me came when she caught me playing a borrowed scratched Chuck Berry record on her record player. The condition of the record dulled her needle. That's when she found another used record player for me to play my collection. I didn't get to play my records much because she was always playing hers. I finally lost interest in anything but jazz, especially jazz guitarist, Kenny Burrell, and jazz vocalist and organist, Jimmy Smith.

Kenny Burrell recorded Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You for his Midnight Blue album, recorded at the Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, on April 6-7, 1963. Every singer who was a singer or was trying to be a singer covered that song. Some were good and some were, well let's say, were not so good. Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You, first recorded by Don Redman on November 5, 1929, in New York, was written by Redman and Andy Razat and later covered by Nat King Cole and Nancy Wilson. Those were the great versions of the song.

I learned my version of Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You by listening to Nancy Wilson and then embellishing in a way that did not please my mother. She said she didn't think I was old enough or mature enough to sing that kind of song when I was 13 years old. "What do you know about that kind of feeling?" She asked. "Your heart has never been out of your chest." What was she talking about? Well, not too many years later I found out.

Kenny Burrell is a UCLA professor and Director of Jazz Studies, where he teaches jazz performance, jazz history, improvisation, composition, jazz combos, contemporary jazz ensemble, and ethnomusicology.

I learned my version of Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You by listening to Nancy Wilson and then embellishing in a way that did not please my mother. She said she didn't think I was old enough or mature enough to sing that kind of song when I was 13 years old. "What do you know about that kind of feeling?" She asked. "Your heart has never been out of your chest." What was she talking about? Well, not too many years later I found out.

Kenny Burrell is a UCLA professor and Director of Jazz Studies, where he teaches jazz performance, jazz history, improvisation, composition, jazz combos, contemporary jazz ensemble, and ethnomusicology.

|

Kenny Burrell, Classroom, UCLA Kenny Burrell MP3 Download Page |

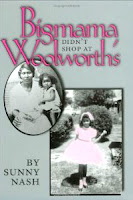

African American National Biography: 12-Volume Set (African American History Reference) Sunny Nash was among 1,700 scholars to contribute to the 12-volume publication |

In my category, Rhythm & Blues (R&B) and Jazz, I used my performing and studio experience, journalism education and understanding of the history of race relations in America, my biographies included jazz guitarist, Kenny Burrell; jazz trumpeter and flugelhorn player, Clark Terry; and pioneer R&B singer-songwriter, Ben E. King. R&B or soul music as it became known and the Civil Rights Movement were closely related during the 1960s.

Gates and Higginbotham hope the books will be used by scholars and will have a place in schools, libraries, and in African American homes. Higginbotham says, “What better way to understand the richness, complexity, and depth of African American history than through biography, because people’s lives are so complex.” The African American National Biography is a compilation of more than 4,000 articles on the contributions of African Americans to the history of the United States and the world. Also on the link, see other related titles on this subject.

Custom Search Kenny Burrell, Jazz, Guitar or other Topics.

Custom Search Kenny Burrell, Jazz, Guitar or other Topics.