Soul music was emerging when Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King led the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

For years, we had watched black-and-white images of singing groups like The Schoolboys win the Ted Mack Amateur Hour, a nationally broadcast talent show, which was our 1960s equivalent of today's American Idol or America's Got Talent or The Voice.

We watched soul music, Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott unfold the Civil Rights Movement against Jim Crow on national television.

However, from 1934 to 1952, Amateur Hour was a national radio broadcast that captivated America. Former Amateur Hour director, Ted Mack, took over the show in 1945 after the originator and producer, Major Bowes, left the show. Bowes died the following year. Ted Mack Amateur Hour, popular among African Americans for being fair to black acts when selecting winning talent, became a hit all over the nation in the black community, where Jim Crow laws were still prevalent.

Music of the day, from Pete Seger to Motown, announced the coming changes to race relations and human rights.

Television and radio became mass media and took hold of young imaginations with news broadcasts, advertising, variety shows and modern music, setting the stage for the next generation. The music industry introduced popular songs and transistor radios with tiny ear buds allowed teens to keep up with the latest hits and unify a national language based on music and fashion followed. My entertainment reflected hit music of the day and classical music of yesterday, and my clothing was my mother's decision. "Can you imagine Jacqueline Kennedy or Rosa Parks ever dressing like Twiggy? my mother asked me once and then answered her own question. "I don't think so."

|

| Rosa Parks Booking Photo |

In 1955, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King and others set the modern movement off with the Montgomery Bus Boycott and soul music set the movement to music.

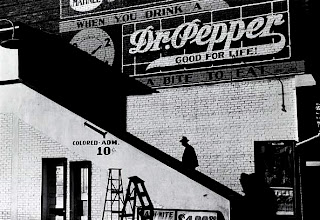

Before the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans had been busy in music and entertainment, and then in the broadcast industry. These early efforts helped to launch and sustain the movement that eventually destroyed Jim Crow laws.

President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. However,it takes more than the stroke of a pen to wipe the heart clean.

Before soul music hit television, there were not many opportunities to see black people showing their talent unless you were able to make to a city to see stage acts. Many venues featured minstrel shows that were frequented by white audiences. In addition, if you were in the South, there may not have been a movie theater that played movies with black actors, musicians and entertainers. In 1939, Ethel Waters made her debut in the experimental television broadcast of a review of her successful Broadway stage play, Mamba's Daughters, and became the first black person to appear on television. That same year, Marian Anderson sang at the Lincoln Memorial, arranged by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, after the the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) refused to allow the singer to perform at Constitution Hall, controlled by DAR in the segregated city of Washington D.C. In 1949, 10 years later, the year I was born, future black religious leader, Louis Farrakhan, at age 16, won the Ted Mack Amateur Hour playing violin.

My childhood a lesson in contrasts watching these figures and events such as Rosa Parks, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the new emerging class of of black entertainers beginning to appear on television in roles other than absent-minded servants and clownish buffoons.

We watched civil rights demonstrations as well as entertainment programming like The Ted Mack Amateur Hour on KBTX TV, the only television station in town. When I was 13, the summer between my seventh and eighth grades, my mother found out Ted Mack was holding auditions in Dallas, unusual because they typically held auditions in New York. My mother asked me if I would like to audition. Insistent upon what she wanted me to do, I knew I had no choice. She really wanted this. I had no idea what my mother was really up to--beauty contests, scholarships and college education.

We watched civil rights demonstrations as well as entertainment programming like The Ted Mack Amateur Hour on KBTX TV, the only television station in town. When I was 13, the summer between my seventh and eighth grades, my mother found out Ted Mack was holding auditions in Dallas, unusual because they typically held auditions in New York. My mother asked me if I would like to audition. Insistent upon what she wanted me to do, I knew I had no choice. She really wanted this. I had no idea what my mother was really up to--beauty contests, scholarships and college education.

Without knowing the full extent of my commitment, I said, "Yes."

I had wanted to sing one of the songs my mother had written, but she said, "No. I don't like the way you sing my songs and play them on piano. You jazz them up too much. They're country songs--not the blues, jazz, gospel or soul music!"

I stared at her and finally whispered, "You shouldn't be writing country songs. We're black!"

"First of all, you don't know what you're talking about," she said. "And second of all, you don't tell me what I should and should not be writing!"

|

Sunny Nash Sings the blues! |

Music on the radio was as segregated as movie theaters, schools, hospitals and other segments of life before the Civil Rights Movement--mostly divided into gospel, country and the blues in the south.

"All music in the south was country music back then," my mother said. "It was radio that segregated black and white southern music. It's separate now and nothing can be done about it. Today, as I read through some the songs she wrote back in the 1950s and 1960s, I hear the country in them.

Moon River is a good song for you to audition with," my mother said. "A very white 'Pop' song that you can't jazz up too much." Johnny Mercer's lyrics and Henry Mancini's music for Moon River won an Academy Award in 1961 for Best Original Song for the movie, Breakfast at Tiffany's, starring Audrey Hepburn. My mother had taken me to see the movie at the segregated Palace Theater. We dreamed large! The style! The clothes! The class! The song also won the 1962 Record of the Year Grammy Award.

Need to know more about American music? Custom search here.

Moon River is a good song for you to audition with," my mother said. "A very white 'Pop' song that you can't jazz up too much." Johnny Mercer's lyrics and Henry Mancini's music for Moon River won an Academy Award in 1961 for Best Original Song for the movie, Breakfast at Tiffany's, starring Audrey Hepburn. My mother had taken me to see the movie at the segregated Palace Theater. We dreamed large! The style! The clothes! The class! The song also won the 1962 Record of the Year Grammy Award.

Need to know more about American music? Custom search here.

My mother wouldn't hear me. "I want you to perform an award-winning song that doesn't require screaming, moaning, growling, mugging and shaking your behind. Musicians shaking and clowning on stage will be the ruination of your generation!"

My mother bought the Moon River sheet music and a 45-rpm recording of Moon River, as sung by Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany's. Turning to me after paying for the sheet music and record, my mother said softly, "I don't care if you win or not," she said. "I will not have uncivilized behavior from you. You are better than that. I want this competition to prepare you for later competitions and education. Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King did not go to jail so that black people could shake their behinds. They've been doing that since day one."

|

| WLAC-AM Rhythm & Blues Late Night DJ, Gene Nobles Randy's Record Shop |

I wanted to sing soul music.

I had listened to Ray Charles and other Rhythm & Blues, Rock & Roll and soul music records, spun by DJ Gene Nobles late at night on the Randy's Record Shop Show, broadcast from WLAC-AM radio station in Nashville, Tennessee. Randy's was a show sponsored by a mail order record store, where people from all over the nation could buy recordings, including those by black artists, who were not available in small records shops throughout the south. Randy's integrated black and white music, defying Jim Crow laws. Although not as important to civil rights as Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Randy's played a significant role in changing society's views of black talent. Later this trend included many artists of soul music like Aretha Franklin and James Brown.

I knew what soul music was supposed to sound like and I wanted to sound like that.

My mother's sister, Clara, had sent me a wristwatch, wireless transistor radio and a number of other gifts from Denver for my birthday. Aunt Clara always sent great gifts for my birthday and Christmas because she always asked, "What do you want, Baby?" She always called me Baby and I got whatever I wanted, as long as it was within reason--a walking-talking doll when I was young, and when I was older, stylish winter coats, jewelry, clothes, electronic gadgets, camera, train tickets to Denver, money, record and magazine subscriptions, books or whatever I asked for.

Soul music and music of all kinds came into play as an integral part in the Civil Rights Movement bringing listeners of different races together.

The transistor radio Aunt Clara sent me received WLAC's 50,000 Watt signal if I placed the radio beside the telephone, which had a cord long enough to drag from the living room into my bedroom without disturbing my mother and father, and my grandmother, whose rooms were in other parts of the house. I placed the tiny earpiece on my pillow and listened all night to popular soul music. My mother didn't buy too much soul music, which became known as Rhythm & Blues (R&B) but, occasionally, I talked her into buying James Brown, Sam Cooke, Gladys Knight & the Pips or Etta James from the record store downtown.

At seven years old, Gladys Knight won Ted Mack's Original Amateur Hour Contest in 1952, went on to stardom with Gladys Knight & the Pips and hit it big in 1961 with Every Beat of My Heart.

|

Gladys Knight

1952, Winner Ted Mack Amateur Hour |

"I wish Eloise was in town," my mother said. "She would play the song the way it should be played." Mrs. King went to visit relatives every summer and was not available. I was not saddened by her absence, having become bored with her classical approach to my voice and piano lessons.

I argued that Mrs. King had taught me to read music and I could rehearse myself. "No," my mother said. My mother said no a lot. "If I let you play Moon River, you will try to play and sing the song black. I want you to sing Moon River straight, like Audrey Hepburn did in the movie or like your cousin Ruby Joyce would sing it." Ruby Joyce was in college on scholarship studying to become an opera singer. She won vocal competitions throughout high school and had performed worldwide while in college. How about singing Moon River like Gladys Knight would sing it, I thought, but did not dare say it.

OK, I finally agreed to sing the song her way, knowing she was not going to give in to my way. I called Raymond, whom I had met at a country church with my father. Raymond was a pianist for one of the visiting choirs. Too young to date, we exchanged phone numbers and talked often on the phone, usually about music. I also had a thriving little music business accompanying local choirs on piano and organ. My mother allowed Raymond to come to the house because she liked hearing the music we made. She also let another fellow I went to school with named, DeWitt McIntosh, visit because he had a really good singing voice, but I did all the accompanying. DeWitt couldn't play piano.

While some of my young neighbors and cousins caught flat-bed trucks that took them off every day in summer to work in area cotton fields, I rehearsed Audrey Hepburn's rendition of the award-winning song, Moon River.

I liked Andy William's version better. I'd heard Andy Williams sing Moon River many times at the beginning of his television show and he sang it at the Academy Awards. I loved it but his version was not in my key and Audrey's Hepburn's was. The key was the only thing I liked about the way she sang the song. But I did like her hair and her clothes. I didn't like the whispery way she sang the song, so I didn't whisper it. I sang it full-voiced like Andy Williams, even mimicked his phrasing, although my mother would not let Raymond play Moon River in his usual gospel fashion. "Play it straight, Ray," she instructed, expecting Raymond to make me hit every note clearly without a hint of improvisation. When she got home from work, she wanted to hear results.

I liked Andy William's version better. I'd heard Andy Williams sing Moon River many times at the beginning of his television show and he sang it at the Academy Awards. I loved it but his version was not in my key and Audrey's Hepburn's was. The key was the only thing I liked about the way she sang the song. But I did like her hair and her clothes. I didn't like the whispery way she sang the song, so I didn't whisper it. I sang it full-voiced like Andy Williams, even mimicked his phrasing, although my mother would not let Raymond play Moon River in his usual gospel fashion. "Play it straight, Ray," she instructed, expecting Raymond to make me hit every note clearly without a hint of improvisation. When she got home from work, she wanted to hear results.

My mother and I took a Greyhound Bus to Dallas where we had relatives to ferry us to and from the Ted Mack audition. My father had several reasons for not taking us, two of which were: he didn't approve of show business and he didn't like or drive in any city that had freeways. It did not matter to him that there may have been a scholarship or cash prizes for a college education waiting for me at the other end.

On our way to Dallas, I stared out of the Greyhound Bus window as we passed cotton fields where cotton pickers had toiled since sunrise and would not be relieved of their duty until sunset. I glanced at my mother and felt ashamed that I had argued with her about the song. That is when it hit me how hard life was for some kids, even if they had a mother. I had never been to a field to pick cotton and knew I never would. My mother had plans for my education.

We had relatives in Dallas who picked us up at the station when we arrived, transported us around the city and put us up over night. She said these were cousins she used to spend summers with when she was a vacationing teenager, when she was not spending the summer with her sister in Denver or her brothers in Houston or California. My mother's exposure to other parts of the country prepared her to raise me for a different type of life. She sent me away for summers, too, in different cities where she used to spend summers when she was a teenager.

In Dallas, my mother and I went to the television studio where the auditions were being held. It was the largest room I'd ever seen, a room with lights overhead, large studio cameras on wheels and cold air blowing from the ceiling.

Although the seats were empty and the cameras were not manned, the lights were on and I was fascinated with the possibility of the place filling up like the live audiences we saw on television at the Ed Sullivan Show. Ed Sullivan hosted many African American acts like the semi-soul girl singers, The Supremes; jazz vocalist, Ella Fitzgerald; singer-dancer, Sammy Davis, Jr.; rhythm crooner, Sam Cooke and others.

My mother and I waited for my turn to perform. I sang the song and everyone seemed to be impressed, but they did not pick me as a finalist. My mother said, "You'll do better next time." I stared at her. She asked, "What? You want me to say how great you were just because you didn't faint from nerves?" She didn't seem at all upset with the judges' decision. We took the Greyhound Bus home, resumed our lives and immediately began to prepare for our next escapade and there were many to follow.

Although the seats were empty and the cameras were not manned, the lights were on and I was fascinated with the possibility of the place filling up like the live audiences we saw on television at the Ed Sullivan Show. Ed Sullivan hosted many African American acts like the semi-soul girl singers, The Supremes; jazz vocalist, Ella Fitzgerald; singer-dancer, Sammy Davis, Jr.; rhythm crooner, Sam Cooke and others.

Need to know more about American soul music? Custom search here.

|

| Bigmama Didn’t Shop At Woolworth’s Sunny Nash Hard Cover Bigmama Didn't Shop at Woolworth's Amazon Kindle Bigmama Didn't Shop at Woolworth's |

"It's not always about winning," my mother said. "It's about showing well and, if you win or lose, do it in a dignified way. In that, you did well."

I learned a great lesson from my mother that first time she took my modest talent out for a spin. The Ted Mack Amateur Hour experience taught me that there is always someone better. My mother was as beautiful and talented as a person could be, but also was an humble person. She got along well with all kinds of people--rich, poor, foreign, domestic, educated and not. I believe she could do this because she was not one of those people who was full of themselves and didn't actually see beyond their own small world. My mother wasn't like that and didn't want me to be like that. "No one is that important," she said. "Except to themselves."

Sunny Nash is the author of Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's (Texas A&M University Press), about life with her part-Comanche grandmother during the Civil Rights Movement. Nash’s book is recognized by the Association of American University Presses as essential for understanding U.S. race relations; listed in the Bibliographic Guide to Black Studies by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York; and recommended for Native American collections by the Miami-Dade Public Library System in Florida.

Also join me on Huffington Post for my comments and discussions on civil rights, race relations, politics, style, entertainment and other pressing issues of the day.

Sunny Nash--author, producer, photographer and leading writer on U.S. race relations in--writes books, blogs, articles and reviews, and produces media and images on U.S. history and contemporary American topics, ranging from Jim Crow laws to social media networking,

Nash uses her book to write articles and blogs on race relations in America through topics relating to her life--from music, film, early radio and television, entertainment, social media, Internet technology, publishing, journalism, sports, education, employment, the military, fashion, performing arts, literature, women's issues, adolescence and childhood, equal rights, social and political movements--past and present—to today's post-racism.

Nash uses her book to write articles and blogs on race relations in America through topics relating to her life--from music, film, early radio and television, entertainment, social media, Internet technology, publishing, journalism, sports, education, employment, the military, fashion, performing arts, literature, women's issues, adolescence and childhood, equal rights, social and political movements--past and present—to today's post-racism.

© 2013 Sunny Nash. All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

~Thank You~

(c) 2014 Sunny Nash

(c) 2014 Sunny Nash

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.