When I learned about Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, civil rights and Jim Crow laws, American schools, movies, television and politics were also black and white in racial terms.

|

| Jim Crow Laws in America |

Martin Luther King changed television pictures of black America by helping place racism in the 1950s and '60s in every living room in the United States .

Black children my age being abused by southern white law officials like Bull Conner did not stop me from watching fifteen-minute national news broadcasts on television. That's what television was for me back then, a medium that led to change in the Jim Crow laws in America.

Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks taught nonviolence in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a tactic used later on television.

What I realized over the years is that black and white people were set in their ways of thinking. And their behavior was based on their ways of thinking. Whites were accustomed to being considered by society as superior; blacks in society were forced to pretend they were inferior. It takes a lot of energy and creativity on both sides of an issue to break old habits. But it can be done.

Television and movies were a big part of shaming people into changing their behavior and changing the way the America looked at itself. Even the staunchest haters and believers in inequality cringed at the sight of themselves and those who represented their views on screen.

As a little girl watching the television images with a family trying to reassure me, I cringed, too. There were days when I was afraid to leave the house. I feared that I would be attacked by a mob. I had never seen a mob except on television. But mobs were real. My Jim Crow school district provided black students no school buses, so we walked to school in groups for security. Going to school and getting whatever education available to African American was never questioned. Education was the way in and the way out--the way into a better life and the way out of a bad life. Even better than primary education was a college education.

College was the goal during Jim Crow laws and still the lesson today.

Television meant that other Americans were seeing what I saw when Martin Luther King spoke on television or little children were attacked by police dogs and high-powered water hoses. Television meant change. Things had to change--change the way we went to school, change the lessons in the school books, change the politics of education and entertainment, change the way we were treated when we went outside our neighborhood. One reason my mother took me to the movies was to illustrate a different lifestyle, not the lifestyle of people I knew, but the lifestyle of people who did not have to worry about being spat upon or police dog attacks initiated by law enforcement officials.

|

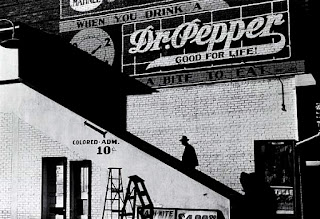

Segregated Movie Theater |

Taking me to the movies, traveling with me to other parts of the nation and reading about Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks and civil rights were my mother's insurance against my being satisfied with Jim Crow.

In 1939, Ethel Waters, star of movies, radio and stage, became the first African American to appear on television, in her own special, "The Ethel Waters Show."

|

Ethel Waters (Article) |

In the early days of television, when the medium was still an experiment, radio was still the primary vehicle for popular dramatic programs and music distribution by jazz vocalists like Ethel Waters. That was before investors thought of television as a profitable new industry to rival radio. There were exceptions. Star of film and radio, Ethel Waters, became the Rosa Parks of television, opening doors for the generation of black actors and filmmakers.

But soon after Waters' television debut, Jim Crow invaded television as it had radio. Many black actors like Ethel Waters either left television and radio in protest or settled for demeaning roles as kitchen help, who sweated over household chores by hand and were the butt of jokes.

My mother subscribed to national news, homemaking and fashion magazines, and newspapers from around the country. That's how my mother was--curious. But more than that, she wanted me to know as much about the world in which I lived as possible, using movies, media and travel to other parts of the country to accomplish her goal. However, when we first started going to the movies, there were white movies in which black actors played subservient roles to white actors; and there were nationally distributed Black Hollywood movies, known as race movies with black casts produced by black filmmakers.

One of the movies my mother and I went to see in 1963 was To Kill a Mockingbird.

I'd already read the book, To Kill a Mockingbird, the year before when I received a copy for my birthday. I loved the way Harper Lee wrote the story of a white father, who was a lawyer, defending a black man who had been accused of raping a white woman. I must confess, though, I hated the theme of the story. Even as a child, I knew of cases where black men were accused of some insult to a white woman.

Lynching and other forms of violence exemplified the lives of many African Americans in the United States during the era of Jim Crow laws, as late as the 1960s, nearly one hundred years after the Civil War was fought to end slavery. Emmett Till was just one of those cases that received national attention from the black media and ignited feelings of horror that led to an inquiry of his murder in the black community when photographs of the Till's brutalized body were published in the black magazine Jet. The NAACP was outraged. Look Magazine brought further attention to the case.

Emmett Till had been beaten and tortured. When he was found, he had a heavy cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire before being tossed into the Tallahatchie River.

|

| Martin Luther King |

Four months after the Emmett Till case, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in 1955 and started the Montgomery Bus Boycott, under the supervision of Martin Luther King The Montgomery Bus Boycott, too, was under the heavy scrutiny of television, magazine and film. This protest and others to follow were spurred into action by the Till case.

In his speech on May 12, 1963, Martin Luther King preached about, ‘‘the crying voice of a little Emmett Till, screaming from the rushing waters." The Emmett Till case was reopened by the Justice Department in 2004.

My family tried to protect me from the harshest of it all but there was no insurance against it. As a result, there were places we didn't go. And that, I learned later, was to avoid the shame of it all. My mother only took me to segregated places that were absolutely necessary to my life--the doctor, bus station, movies, school and other public facilities where I needed to go. We didn't eat out very often. Restaurants required us to enter through a rear door, sit in an inferior location or walk up to an outdoor window to order and receive food with no place on premises to eat. My cousin, Joyce, reminded me the other day that at the bus station in her hometown required African Americans to eat their orders in the baggage room sitting at discarded desks retrieved from a local school.

|

| Movie Theater Austin, Texas 1930 |

One sacrifice my mother would not make was the movie theater. On Saturday mornings we got dressed in our best clothes and walked the couple of miles downtown. Now, we didn't dress like movie stars, but my mother liked nice clothes. In fact, my mother bought nice furnishings and other elements of home decor, and was the cleanest and most organized person I ever met. "Just because someone is poor doesn't mean they have to live in squalor," she always said.

In summer, we had several floral sundresses each. In winter we snuggled into coats or rain gear and boots my father bought. My father worked on Saturday mornings and my mother had no drivers license at that time. Movies did not interest my father. He was an outdoors person and said, "I wouldn't sit that long in a dark room, even if I could sit downstairs with the white folks.". By the time my mother and I walked downtown our feet hurt. I felt like Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott protesters. the difference was, we didn't have a public transit system in our town.

|

| Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's by Sunny Nash |

Excerpt below from “Movies—Not Just Black-and-White,” an essay in my book, Bigmama Didn’t Shop At Woolworth’s (Texas A&M University Press).

I write about the first time my mother took me to lunch and the movies. It was about to rain that Saturday but my young mother agreed to take her little daughter to the movies anyway:

Without reply, my mother dug into her tiny cloth coin purse and paid. Time passed as slowly as it could before her change and our food arrived. “Y’all can’t eat in here,” the cook said. Without a word, my mother grabbed my hand and dragged me to the back door. As we stood outside and ate in silence, I thought I saw a tear sparkle on my mother’s cheek as the day’s last sunlight stroked her face. With a few drops of rain falling on us, we took the short walk to the Palace Theater and stood at the ticket window outside the main lobby. The aroma of buttered popcorn floated through the little round hole in the glass where the ticket woman worked. To avoid getting wet in the shower, the moviegoers dashed through a glass front door into a dry, comfortable lobby filled with tiny white lights, velvet draperies, and red carpet. By the time my mother and I got our tickets, big drops of rain were splashing down on our heads. With her hair heavy with water, sliding into her face, my mother dug into her tiny cloth coin purse and paid. The little blue door on the outside of the theater slammed us inside the darkest place I’d ever been—like a coffin, I thought, holding my mother’s hand.

|

Littie Nash |

My mother, Littie Nash, wrestled with Jim Crow laws during the 1950s and 1960s, while giving me the life of a little princess with imagination and without the luxury of having a lot of money for stylish fashions...Littie, the ultimate stage mother, did not waste compliments on me or anyone else. She reserved accolades to celebrate real accomplishments, not just because I dragged myself out of bed before noon on Saturday or because I made an 'A' on my report card. "Some things you have to do," she said. "And those things pass, not without notice, but without an all-day hullabaloo."

To support my efforts, my mother sponsored piano, ballet, tennis and swimming lessons, dance performances, recitals, literary and classical music club memberships, summer camps, school trips and science fair exhibits, still managing to squeeze out of our tight budget money for the dentist to install braces on my teeth and pay for my health insurance. It took a great deal of courage to live with dignity and raise me to have aspirations. About my upbringing, Littie got it right, although I took detours of my own along the way. Read more at: Great Mothering in Jim Crow's World

|

Sunny Nash |

© 2012 Sunny Nash

All Rights

Reserved Worldwide.