Riding the waves of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Woolworth's sit-ins integrated lunch counters across the nation and helped to destroy Jim Crow laws.

Woolworth sit-ins at Greensboro, North Carolina, lunch counters in 1960 led set off the most significant civil rights movement of twentieth century America, after Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King led Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, both of which sounded knell to Jim Crow laws.

Four well-dressed black college freshmen, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr. (later known as Jibreel Khazan), and David Richmond, from segregated North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College, known as the Greensboro Four, challenged Jim Crow when they sat down at the Woolworth’s lunch counter and asked politely to be served, sparking similar protests and racial demonstrations across the nation in the south and the north.

The Greensboro Four from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College protested in a similar style to that of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the style later perfected by the non-violent protest style of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in the streets of the Deep South that led up to his I Have A Dream Speech. Non-violent protest methods, taught to those who would participate, were rehearsed and scripted so that tempers would be kept in line and escalation of violence would be one sided to highlight hatred directed toward innocent people marching or sitting for their rights. This non-violent style of protest was designed to be captured by a new broadcast medium, called television, much more effective than sound-only radio.

|

| Photo: Rosa Parks Montgomery Bus Boycott 1956 |

The young college freshmen, who had earned the deserving title of the Greensboro Four, were refused service at the lunch counter because Woolworth 's headquarters had decreed that the company policy was “to abide by local custom.” The persistence of the four male students every day following that first day caused other students, including female and white students, to join them. As news spread over the nation, similar actions were repeated in other cities across America, bringing down the old Jim Crow laws that represented segregation and overt discrimination against African Americans and other non-white people.

Offering an unusually intimate portrait of four men whose moral courage at ages 17 and 18 not only changed public accommodation laws in North Carolina but also served as a blueprint for non-violent protests throughout the 1960s, FEBRUARY ONE: The Story of the Greensboro Four reveals how these idealistic college students became friends and inspired one another to stage the sit-in, and how the burden of history has impacted their lives ever since.

At the time that the protest at Woolworth's in Greensboro was taking place in 1960, it was five months before my eleventh birthday. Five years earlier, I remember my mother talking about Rosa Parks and showing me pictures of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in a magazine. I had no real idea what I was looking at six years old. But I did understand the signs that read Colored Served in Rear.

|

| Signs of the Time: Colored Served in Rear |

| Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka: A Brief History with Documents (Google Affiliate Ad) |

I even knew about the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Brown v. the Board of Education. That was a year before my mother enrolled me in first grade. She didn't didn't try hiding things from me even when I was little and she was trying figure out how Brown would affect me. I saw the pictures in the newspaper. My mother took black newspapers from other cities because she said our local paper didn't print anything about us unless it was bad. She needed to know whether I would have to go to a different school than the one she knew about. Brown didn't affect me. Schools remained segregated through my high school graduation.

Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court decision that mandated the desegregation of U.S. schools, is popularly seen as a hallmark of American justice. But author and professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego, Peter Irons, surveys recent U.S. history to reveal a quite different picture: many states have found ways to delay implementation of, or totally evade, the ruling. .

In 1955 and 1956, the Montgomery Bus Boycott brought Alabama buses to a halt. I was in first grade when I heard my teachers whispering about a woman named Rosa Parks who had refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus and started the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

At 10 years old, I was very aware of the treatment of black people in stores, movies and other private and public places. In fact, before I went to the first grade, my grandmother taught me to read 'white only' and 'colored' before I had learned to read any other words. When I did attend school, they were segregated. I could see as we passed in the car that those schools for white students were bigger, and better constructed and landscaped than the schools for black students. But I was also aware of the changes taking place.

We were never issued new text books. The books delivered to my schools were hand-me-down books from the white schools. Most of the books had been used to a frayed condition and had been deliberately defaced, I believed, because of the defamatory words written in the margins. My family, especially my grandmother, and my teachers, many of whom were descendants of former slaves, encouraged me to erase what I could from the margins of the defaced textbooks and ignore the rest, assuring me that it was the information printed inside the book that mattered.

|

| Post-Civil War Black School Virginia 1900s |

Although my elementary school was not as roomy, comfortable or well equipped as their schools, I believe my education rivaled any of its day, black and white. The reason I say that is because, years later, I graduated from a large, white university and had no trouble with the course work. One of my professors told me early on I should leave. "Your education could not possibly have prepared you for university work," he said. Fortunately, I didn't listen. As a matter of fact, I never listened to anyone who told me I wouldn't make it there.

|

| Integration after 1954 Brown Decision Promise of Justice: Essays on Brown V. Board of Education by Stewart, (Google Affiliate Ad) |

Finally, everyone got used to seeing me around and left me alone about it, really alone. No one wanted me in their study group until they learned that I was making A's and then a lot of people wanted me in their study groups. No thanks.

Somehow, I never took it personally, a skill I learned from my grandmother. "Keep your emotions out of the matter," Bigmama would say when I complained about something. "Getting emotional takes you out of control." So, when I was in college with all those white students who were supposed to know so much than me, I concentrated on getting the education, the grades and my degree.

I'm happy I didn't make a huge stink of every slight I perceived against me. Having lived in a segregated and oppressive society, it would have been natural for me to consider hateful-sounding things to be hateful. But it bored me to try and figure out the meaning of every breath uttered from every mouth around me. Sometimes slights are real, but most often people are a lot like me--not spending much time thinking about anything but themselves, their families, their problems, their own lives and how they are going to get from here to there. Ignoring and redefining perceived slights frees the mind to move ahead in life. This is true for everyone, black or white, who may have an insecurity of some kind. And believe me, when I graduated from college, I left a string of insecure people behind, both professors who warned me to leave and white students I had out-performed.

|

| All-Black Elementary School Tennessee 1940s Library of Congress |

The problem with education for black students in the past in most parts of the United States during the pre-civil rights era is that the education reserved by black students in other parts of the nation sometimes did not measure up to the education of their white counterparts. When I was a child, I knew inferior education for black students had been true throughout history since Reconstruction after the Civil War. In rural areas, especially in the south but not exclusive to the south, poor education meant keeping future opportunities inaccessible for the nation's pool of cheap labor.

|

| Mississippi Plantation Cotton Pickers Library of Congress |

If these people were led to believe they had no opportunity and had no hope of it, maybe they would expect no opportunity, would adapt to their condition and reach for no higher goals. In the minds of the ruling class, poor education and oppression were enough to keep many African Americans, poor white Americans and Mexican Americans in their places down on the farm, which kept them from adding to the competition growing in response to the influx of European and other immigrants into the nation's already crowded urban workforce. One method of keeping the rural population rural and out of the cities was to create a system of virtual bondage through sharecropping agreements, a method introduced immediately after the Civil War, but not restricted to former slaves. By the 1930s, during the Great Depression, there were nearly two million sharecroppers and tenant farmers in the rural South--black, white and brown--who experienced pseudo slavery, in that, they were imprisoned on large farms by commonly used unfair bookkeeping practices by their landlords.

|

| White Sharecroppers 1930s Photo by Dorothea Lange Library of Congress You Have Seen Their Faces by Caldwell, Erskine/ Bourke-White, Margaret (Google Affiliate Ad) |

After the Civil War, former slaves rushing from plantations to test freedom caused a shortage of farm workers and left vacant slave quarters that white sharecroppers filled. The sharecropping system gave sharecroppers shelter, sometimes in former slave quarters, mules, access to land, seed to raise a crop, usually cotton in the South, and farm store credit, leading to insurmountable debt. Landowners got a share and sharecroppers received a share against their debt. In some instances, sharecropping families remained in arrangements into the 1960s civil rights era when lands were abandoned and sold.

Generations of conditioning by tyrannical lords of an uncivilized social order set up a framework for a continued system of labor control and suppression of fair earnings. When people's livelihoods are kept at a minimum with no increases ever, then it would be easy for American society to enter an insiders' agreement, for the good of the rest, to keep certain people down on the farm working as sharecroppers and tenant farmers for less than subsistence wages, accepting the menial lifestyle and being imprisoned on the farms by dishonest bookkeeping. However, the agreement is good only as long as everyone involved allows the framework to remain in place.

|

| Women Joined the Greensboro Woolworth's Sit-ins and Sit-ins around the Nation Library of Congress |

Oppressed black Americans, were labeled by the color of their skin.

Oppressed whites could simply walk away from their oppression, not having been labeled by the color of their skin. However, black people had inherited hope for a better life from former slaves and the children of former slaves who had lived through the unimaginable and passed on the desire to rise to me and others like the Greensboro Four, who sat down at the segregated Woolworth's lunch counter in 1960. Because Brown v. the Board of Education decision in 1954 had ended segregation put into place in 1896 by Plessy v. Ferguson, the Woolworth's sit-ins and demonstrations were not just about being served a meal. Among the issues being protested wholesale also included segregation of facilities and inferior education. As good as my education may have been when I was in elementary school in 1960, it did not guarantee that I would get a good job at the end of high school, even if I went on to college.

The most professional position I could train for at that time was schoolteacher."And be glad to get it," the old timers would say. Or I could train to serve my community in some capacity such as a hairdresser, barber or midwife. Other African Americans owned businesses such as shoeshine benches, clothing stores, restaurants, grocery stores, nursery schools, insurance companies, funeral homes, clothes cleaners or they were preachers.

|

| Black Southern Family 1940s In Front of Their Home Library of Congress |

A good income was still out of reach for African Americans when I was still in school, although, that did not stop the hard-working people in African American neighborhoods from enjoying good lives. There seemed to be a different value system in place then, a value system that included raising children who had no trouble knowing right from wrong, helping people in need and growing a nice vegetable garden. Everyone had a nice vegetable garden and we knew exactly what we were eating.

African Americans and those whites who sympathized with the plight of the descendants of former American slaves became weary of waiting for things to be different for so many people who had waited so long. There had been the Brown Decision in 1954 and the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, sparked by Rosa Parks. The wait was coming to an end as national media coverage indicated big changes on the horizon. Below, see a video of historical development that came from the Woolworth's sit-ins, including film of civil rights marchers and pictures of the events during the protest.

Segregation was a way of life until Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King found a vehicle, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, to change that way of life.

That's why so many whites joined in the demonstrations. Others were afraid to show their change of heart for fear of being ostracized by their own communities. I'm not saying everyone has changed and we are all living happily without prejudice ever after. I am saying that we have come a long way. And I recognize that and I am happy about that. But we must go the rest of the journey in all human relations, including those having to do with race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, physical ability and economic status.

|

| Allan Preyer III |

When I wrote my book, Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's, there was no FaceBook, which requires precautions against political correctness. because communications one key stroke away from insulting someone.

| Follow Sunny Nash |

Communications have changed and are light years ahead of the tools I used writing my book and columns on a personal computer. I had no idea how easy it would become to inflict political incorrectness.

Also join me on Huffington Post for my comments and discussions on civil rights, race relations, politics, style, entertainment and other pressing issues of the day.

|

| Join Sunny Nash on Huffington Post |

Frank Winfield Woolworth started Woolworth’s in 1878 with a $300 loan, becoming the owner of one of the nation’s largest retail chains through a “five and dime” concept, changing forever how Americans shop. However, when the storekeeper opened his first store, the tight grip of Jim Crow was firmly around the neck of the United States and it is no wonder that his store and most other facilities in the nation were segregated for nearly 100 years to come.

From Woolworth’s lunch counter sit-ins in 1960, the non-violent movement spread to other cities in North Carolina and then across the nation and challenged segregation in the United States. Many of the demonstrators who affected the demise of the Jim Crow system were white students, who sat at lunch counters, marched in the streets and were arrested alongside black students protesting separate but equal. Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States Constitutional law justifying a system of segregation of services, facilities and public accommodations by race, as long as the accommodations for each group remained equal.

My grandmother, Bigmama, whom I write about in my book, Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's, did not shop at Woolworth’s for a couple of reasons. Bigmama didn’t trust the quality of anything that cost a nickel or a dime and she didn’t like the idea that she, as a woman of part Native American and African American heritage, didn’t have full access to everything in the store available to other customers.

|

| International Civil Rights Center & Museum Greensboro, North Carolina |

Chosen by the Association of American University Presses as one of its essential books for understanding race relations in the United States, Bigmama Didn’t Shop At Woolworth’s (Texas A&M University Press) is also listed in the Bibliographic Guide to Black Studies by the Schomburg Center in New York and recommended for Native American collections by the Miami-Dade Public Library System in Florida.

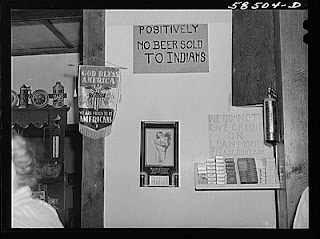

Between 1876 and 1965, Jim Crow laws legalized segregation of all public and private facilities and services and blatant discrimination against African Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans and Mexican Americans in the United States. Taking its name from a stage show character played by whites in black face, Jim Crow characters entertained white audiences and Jim Crow laws grew into a body of black codes applied against former slaves and other non-white Americans and their offspring well into the twentieth century. Native Americans are the most harshly affected by institutionalized racism, according to Worldwatch Institute, which notes that "317 reservations are threatened by environmental hazards. While formal equality has been legally granted, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders remain among the most economically disadvantaged groups in the country, and suffer from high levels of alcoholism and suicide."

This is an excerpt from an essay in my book, Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's, “My Grandmother’s Sit-in,” in which Bigmama and I went to visit a relative in the Navasota (Texas) hospital: Afraid that my grandmother and I would be arrested or worse, my blood ran cold sitting under the “White Only” sign. I was proud and ashamed at the same time but too terrified to look up and see other people watching us.

“I was about your age when the Supreme Court used the railroad to legalize what they called ‘separate but equal,’” Bigmama said. “It was 1896. Plessy v. Ferguson made things separate, but it sure didn’t make them equal.”

Bigmama shifted in her chair and whispered, “All Mr. Plessy wanted was a first-class train ticket. Well, he could spend first-class money on a first-class ticket, but Jim Crow said he couldn’t put his black behind in a first-class seat.”

“Who’s Jim Crow?” I asked.

|

| Sign of the Times: Positively No Beer Sold to Indians |

JOIN MY SITE

|

| Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's by Sunny Nash |

This is an excerpt from an essay in my book, Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's, “My Grandmother’s Sit-in,” in which Bigmama and I went to visit a relative in the Navasota (Texas) hospital: Afraid that my grandmother and I would be arrested or worse, my blood ran cold sitting under the “White Only” sign. I was proud and ashamed at the same time but too terrified to look up and see other people watching us.

“I was about your age when the Supreme Court used the railroad to legalize what they called ‘separate but equal,’” Bigmama said. “It was 1896. Plessy v. Ferguson made things separate, but it sure didn’t make them equal.”

Bigmama shifted in her chair and whispered, “All Mr. Plessy wanted was a first-class train ticket. Well, he could spend first-class money on a first-class ticket, but Jim Crow said he couldn’t put his black behind in a first-class seat.”

“Who’s Jim Crow?” I asked.

|

| Jim Crow Minstrel Character Black Face Post Card |

“Was Jim Crow before or after the South lost their war?” I asked softly, hardly breathing.

"The North may have won the Civil War in the history books, but the South didn’t lose,” whispered Bigmama, smiling with a frown between her eyes as she often did. “The North gave the South everything the South was fighting to keep; because the North, the South, the West and the East all wanted the same thing—us in a low place.” My grandmother got up, smoothed her coat, and politely nodded to the other stunned hospital guests. “I’m going now,” she said. “I never stay long where I’m not wanted.”

Buy: Bigmama Didn’t Shop At Woolworth’s by Sunny Nash

|

| Sunny Nash |

Chosen by the Association of American University Presses as one of its essential books for understanding race relations in the United States, Bigmama Didn't Shop At Woolworth's (Texas A&M University Press) by the award-winning author, Sunny Nash, is also listed in the Bibliographic Guide to Black Studies by the Schomburg Center in New York and recommended for Native American collections by the Miami-Dade Public Library System in Florida.

by Sunny Nash

Related Articles by Sunny Nash

© 2011 Sunny Nash

All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

~Thank You~

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.